All Resources

San Andreas-sized Strike-slip Fault on Europa

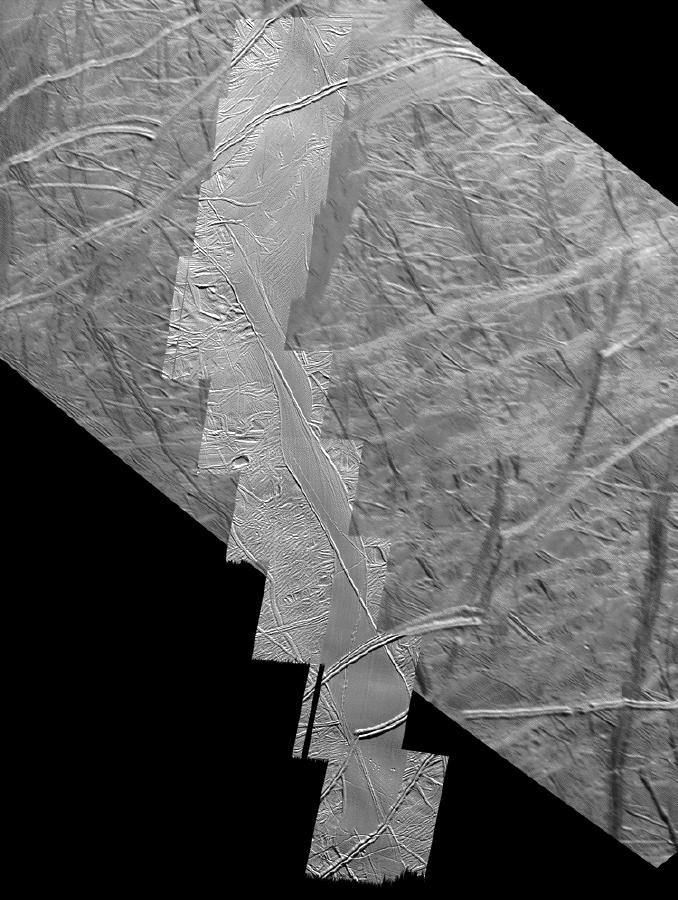

This mosaic of the south polar region of Jupiter's moon Europa shows the northern 180 miles (290 kilometers) of a strike-slip fault named Astypalaea Linea. The entire fault is about 500 miles (810 kilometers) long, about the size of the California portion of the San Andreas fault, which runs from the California-Mexico border north to the San Francisco Bay.

In a strike-slip fault, two crustal blocks move horizontally past one another, similar to two opposing lanes of traffic. Overall motion along the fault seems to have followed a continuous narrow crack along the feature's entire length, with a path resembling steps on a staircase crossing zones that have been pulled apart. The images show that about 30 miles (50 kilometers) of displacement have taken place along the fault. The fault's opposite sides can be reconstructed like a puzzle, matching the shape of the sides and older, individual cracks and ridges broken by its movements.

The red line marks the once active central crack of the fault. The black line outlines the fault zone, including material accumulated in the regions which have been pulled apart.

Bends in the fault have allowed the surface to be pulled apart. This process created openings through which warmer, softer ice from below Europa's brittle ice shell surface, or frozen water from a possible subsurface ocean, could reach the surface. This upwelling of material formed large areas of new ice within the boundaries of the original fault. A similar pulling-apart phenomenon can be observed in the geological trough surrounding California's Salton Sea, in Death Valley and the Dead Sea. In those cases, the pulled-apart regions can include upwelled materials, but may be filled mostly by sedimentary and eroded material from above.

One theory is that fault motion on Europa is induced by the pull of variable daily tides generated by Jupiter's gravitational tug on Europa. Tidal tension opens the fault and subsequent tidal stress causes it to move lengthwise in one direction. Then tidal forces close the fault again, preventing the area from moving back to its original position. Daily tidal cycles produce a steady accumulation of lengthwise offset motions. Here on Earth, unlike Europa, large strike-slip faults like the San Andreas are set in motion by plate tectonic forces.

North is to the top of the picture and the sun illuminates the surface from the top. The image, centered at 66 degrees south latitude and 195 degrees west longitude, covers an area approximately 185 by 125 miles (300 by 203 kilometers). The pictures were taken on Sept. 26, 1998 by Galileo's solid-state imaging system.