Mission Updates | June 27, 2022

Mission Dispatch: Wiring Europa Clipper's Propulsion Module

She went from being a commercial electrician to wiring the electrical system for NASA’s Europa Clipper propulsion module — the “workhorse” that has the enormous task of getting the spacecraft into orbit around Jupiter.

Carlisa Drew, an electrician by trade, was accustomed to wiring simple single cables. But in her role as lead hardware development technician at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Maryland, Drew worked on an assembly of specially bundled electrical wires and connectors called a “harness,” which powers Europa Clipper’s propulsion module and its payload. The harness’s trunk climbs the spine of the propulsion module like a central nervous system, sending out branches of electrical wires around the cylindrical frame to power various parts of the spacecraft.

In 2030, after nearly six years of cruising through the solar system, Europa Clipper will come hurtling toward Jupiter so fast that it could swing right past the gas giant and continue out to deep space if it is not captured in Jupiter’s orbit. The propulsion module that Drew wired is designed to rein in the speed, so the spacecraft can safely orbit Jupiter and achieve its flyby science to determine if the icy moon Europa could host conditions favorable for life.

Wiring spacecraft was not Drew’s intended field of expertise.

In high school, she thought she’d pursue a career in business. But as Drew learned more about the field, she realized it wasn’t for her. Her school offered informational videos and corresponding hands-on demonstrations for students to try various trades, and Drew’s school counselor suggested she start there. Drew tried some trades where she’d get to work with her hands, since that’s what she had always preferred.

Baking? “I don’t want to do this.”

Brick laying? “Too big and dusty.”

Electrical work? “I get to read prints! I get to build things!”

Drew was hooked. Through an apprenticeship program offered by an electrical workers union, she spent five years working during the day and studying at night. Upon completing the apprenticeship, Drew started work as a commercial electrician.

After 15 years of doing electrical work mostly outdoors, however, Drew noticed the winters were feeling too cold and the summers too hot. She was looking for work that would allow her to be mostly indoors. Drew didn’t know at the time that she would end up working in some of the most strictly climate-controlled environments on Earth.

For a time, Drew worked for a Baltimore cable company, where she learned much of what she uses today. Her electrician mentors helped, too, along with training programs at APL that Drew describes as “excellent.”

When hired at APL, Drew expected to work on cables for ground support or testing. “I never thought that I would be building cables that would one day end up going into space.”

When given the opportunity to be the lead harness technician for the propulsion module, she was thrilled. “In the beginning, I felt pretty confident,” she says, chuckling. “So they handed me the plans and then cut me loose.”

Wiring the propulsion module was no small task. Weighing about 150 pounds (68 kilograms), the harness that Drew helped build contains thousands of electrical wires and connectors. If placed end to end, these components would stretch almost 2,100 feet (640 meters) — enough to twice wrap around the perimeter of a football field.

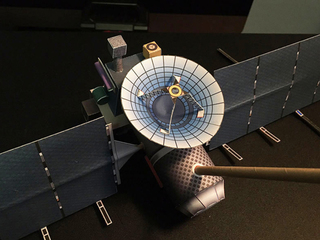

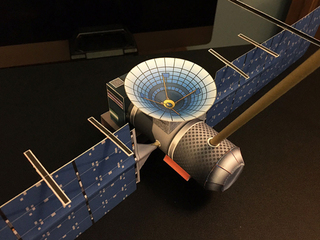

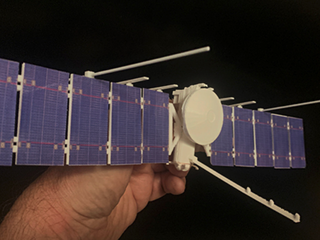

Europa Clipper’s propulsion module has a total of 24 engines, 16 which are rear-facing. At about 10 feet (3 meters) tall and 5 feet (1.5 meters) in diameter, the module is about the size of an SUV.

Though Drew was the lead harness technician for the job, she didn’t do it alone and is grateful to her fellow team members at APL. “For my first mission, I couldn’t have been put with a better group of people.”

She and several colleagues spent about a year assembling the harness on a mock-up propulsion module, roping wires together, attaching pins to the ends of the wires, and inserting the pins into connectors. They had “wrapping parties,” in which they would cover connectors with as many as 18 layers of sheeted copper or lead meant to protect them from Jupiter’s harsh radiation environment.

“The amazing part of this effort is the people who designed the system,” Drew says. “Having wires all run in every direction to the different components — it’s a remarkable feat.”

Drew and her team have finished installing the wiring harnesses on the propulsion module. In early June, a cargo plane carried the propulsion module, along with the radio frequency (RF) module, to NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California where they will be integrated with the remainder of the spacecraft.

“It’s bittersweet,” Drew says, of completing the wiring for the propulsion module. “It’s the coolest thing I’ve worked on in my entire life.”