All Resources

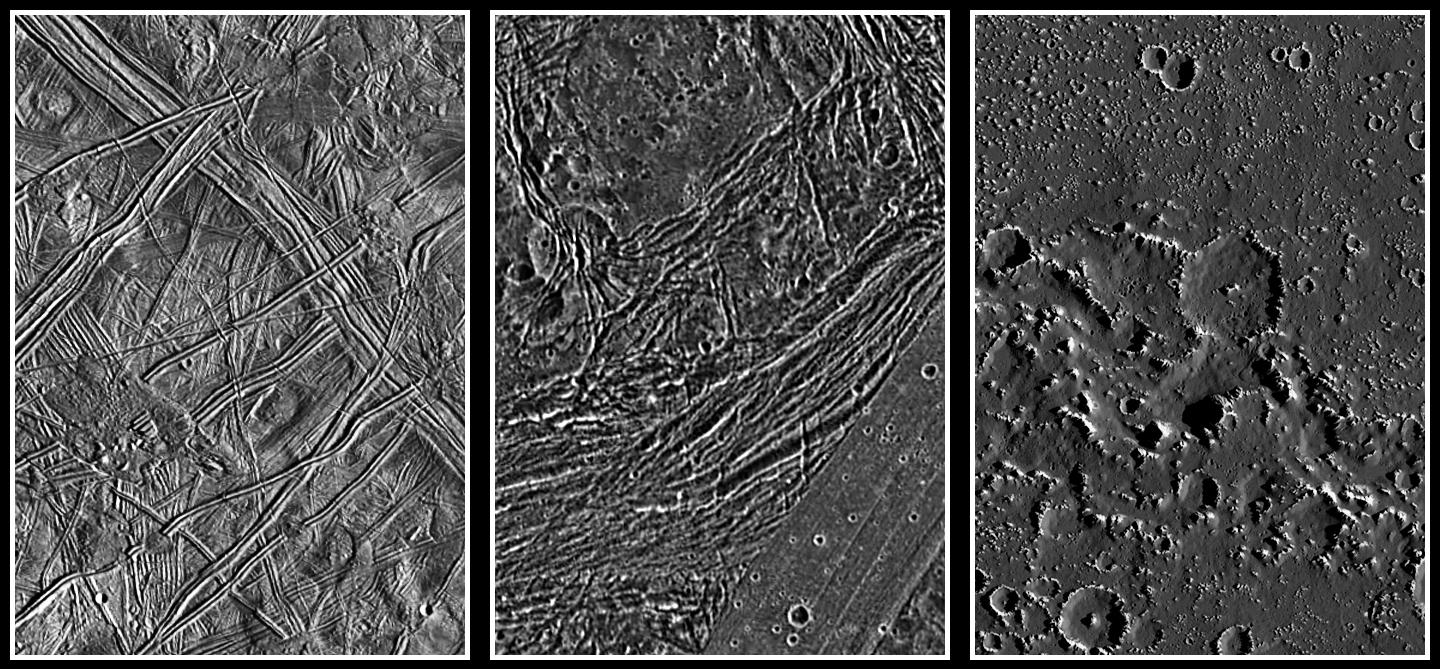

Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto: Surface Comparison at High Spatial Resolution

These images show a comparison of the surfaces of the three icy Galilean satellites, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto, scaled to a common resolution of 492 feet (150 meters) per picture element (pixel). Despite the similar distance of 497 million miles (800 million kilometers) to the Sun, their surfaces show dramatic differences. Callisto (with a diameter of about 3,000 miles or 4,817 kilometers) is "peppered" by impact craters, but is also covered by a dark material layer of so far unknown origin, as seen here in the region of the Asgard multi-ring basin. It appears that this layer erodes or covers small craters. Ganymede's landscape is also widely formed by impacts, but different from Callisto, much tectonic deformation can be observed in the Galileo images, such as these of Nicholson Regio. Ganymede, with a diameter of about 3,300 miles or 5,268 kilometers (one-and-a-half times larger than the Earth's moon), is the largest moon in the solar system. Contrary to Ganymede and Callisto, Europa (diameter 1,940 miles or 3,121 kilometers) has a sparsely cratered surface, indicating that geologic activity took place more recently. Globally, ridged plains and the so-called "mottled terrain" are the main landforms. In the high-resolution image presented here showing the area around the Agave and Asterius dark lineaments, older ridges dominate the surface, while a small part of the younger mottled terrain is visible to the lower left of the image center.

While all three moons are believed to be nearly as old as the solar system (4.5 billion years), the age of the surfaces, i.e. the time since the last major geologic activity took place, is still subject to debate. Without having surface samples in hand, the only method to roughly determine a planet's or satellite's geologic surface age is by crater counting. However, assumptions about the impactor fluxes must be made based on theoretical models and possible observations of candidate impactors such as asteroids and comets. Asteroids should have been very common in the early days of the solar system, but this source should have been largely exhausted by about 3.8 billion years before present. For comets, the impactor flux is believed to be rather constant throughout the whole lifetime of the solar system, meaning that the probability of an impact of a large comet is similar today as it was, say, four billion years ago.

Assuming the asteroids have been the dominant bodies that impacted the Galilean satellites (which is believed to be the case on the Moon, the Earth, and other inner solar system bodies as well as within the asteroid belt itself), the surfaces of Ganymede and Callisto must be old, roughly four billion years. In this case, the Europan surface would by comparison have a mean age of one-hundred to several-hundred million years. Low-level geologic activity on Europa might be possible, but Ganymede and Callisto should be geologically dead. Assuming on the other hand that comets have been the main impactors in the Jovian system, Callisto's surface would still be determined to be old, but Ganymede's youngest large craters would have been created only about one billion years ago. Europa's surface in this model should be very young, with this satellite being geologically quite active even today.

The images were taken by the Solid State Imaging (SSI) system on NASA's Galileo spacecraft. They were processed by the Institute of Planetary Exploration of the German Aerospace Center (DLR) in Berlin, Germany, and scaled to a size of 490 feet (150 meters) per pixel. North is up in all images. The spatial resolution of the original data was 590 feet (180 meters) per pixel for Europa and Ganymede and 295 feet (90 meters) per pixel for Callisto. The Europa image was taken during Galileo's 6th orbit, the Ganymede image during the 7th, and the Callisto image during the 10th orbit.